KRISTALNACHT

A NATIONWIDE NAZI POGROM,

NOVEMBER 9-10, 1938

From: KRISTALLNACHT: A NATIONWIDE POGROM,

NOVEMBER 9-10, 1938

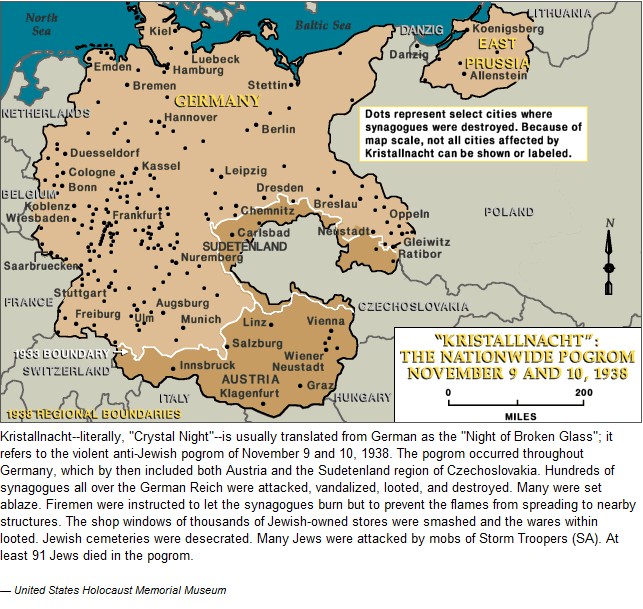

Kristallnacht -- literally, "Night of Crystal," is often referred to as the "Night of Broken Glass." The name refers to the wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms which took place on November 9 and 10, 1938 throughout Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia recently occupied by German troops. Instigated primarily by Nazi Party officials and members of the SA (Sturmabteilungen: literally Assault Detachments, but commonly known as Storm Troopers) and Hitler Youth, Kristallnacht owes its name to the shards of shattered glass that lined German streets in the wake of the pogrom-broken glass from the windows of synagogues, homes, and Jewish-owned businesses plundered and destroyed during the violence.

In its aftermath, German officials announced that Kristallnacht had erupted as a spontaneous outburst of public sentiment in response to the assassination of Ernst vom Rath, a German embassy official stationed in Paris. Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew, had shot the diplomat on November 7, 1938. A few days earlier, German authorities had expelled thousands of Jews of Polish citizenship living in Germany from the Reich; Grynszpan had received news that his parents, residents in Germany since 1911, were among them.

Initially denied entry into their native Poland, Grynszpan's parents and the other expelled Polish Jews found themselves stranded in a refugee camp near the town of Zbaszyn in the border region between Poland and Germany. Already living illegally in Paris himself, a desperate Grynszpan apparently sought revenge for his family's precarious circumstances by appearing at the German embassy and shooting the diplomatic official assigned to assist him.

Vom Rath died on November 9, 1938, two days after the shooting. The day happened to coincide with the anniversary of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, an important date in the National Socialist calendar. The Nazi Party leadership, assembled in Munich for the commemoration, chose to use the occasion as a pretext to launch a night of antisemitic excesses. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, a chief instigator of the pogrom, intimated to the convened Nazi 'Old Guard' that 'World Jewry' had conspired to commit the assassination and announced that, "the Führer has decided that … demonstrations should not be prepared or organized by the Party, but insofar as they erupt spontaneously, they are not to be hampered."

Goebbels' words appear to have been taken as a command for unleashing the pogrom. After his speech, the assembled regional Party leaders issued instructions to their local offices. Violence began to erupt in various parts of the Reich throughout the late evening and early morning hours of November 9-10. At 1:20 a.m. on November 10, Reinhard Heydrich, in his capacity as head of the Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei) sent an urgent telegram to headquarters and stations of the State Police and to SA leaders in their various districts, which contained directives regarding the riots. SA and Hitler Youth units throughout Germany and its annexed territories engaged in the destruction of Jewish-owned homes and businesses; members of many units wore civilian clothes to support the fiction that the disturbances were expressions of 'outraged public reaction.'

Despite the outward appearance of spontaneous violence, and the local cast which the pogrom took on in various regions throughout the Reich, the central orders Heydrich relayed gave specific instructions: the "spontaneous" rioters were to take no measures endangering non-Jewish German life or property; they were not to subject foreigners (even Jewish foreigners) to violence; and they were to remove all synagogue archives prior to vandalizing synagogues and other properties of the Jewish communities, and to transfer that archival material to the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst, or SD). The orders also indicated that police officials should arrest as many Jews as local jails could hold, preferably young, healthy men.

The rioters destroyed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many synagogues burned throughout the night, in full view of the public and of local firefighters, who had received orders to intervene only to prevent flames from spreading to nearby buildings. SA and Hitler Youth members across the country shattered the shop windows of an estimated 7,500 Jewish-owned commercial establishments, and looted their wares. Jewish cemeteries became a particular object of desecration in many regions.

The pogrom proved especially destructive in Berlin and Vienna, home to the two largest Jewish communities in the German Reich. Mobs of SA men roamed the streets, attacking Jews in their houses and forcing Jews they encountered to perform acts of public humiliation. Although murder did not figure in the central directives, Kristallnacht claimed the lives of at least 91 Jews between 9 and 10 November. Police records of the period document a high number of rapes and of suicides in the aftermath of the violence.

As the pogrom spread, units of the SS and Gestapo (Secret State Police), following Heydrich's instructions, arrested up to 30,000 Jewish males, and transferred most of them from local prisons to Dachau, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and other concentration camps. Significantly, Kristallnacht marks the first instance in which the Nazi regime incarcerated Jews on a massive scale simply on the basis of their ethnicity. Hundreds died in the camps as a result of the brutal treatment they endured; most obtained release over the next three months on the condition that they begin the process of emigration from Germany. Indeed, the effects of Kristallnacht would serve as a spur to the emigration of Jews from Germany in the months to come.

In the immediate aftermath of the pogrom, many German leaders, like Hermann Göring, criticized the extensive material losses produced by the antisemitic riots, pointing out that if nothing were done to intervene, German insurance companies-not Jewish-owned businesses-would have to carry the costs of the damages. Nevertheless, Göring and other top Party leaders decided to use the opportunity to introduce measures to eliminate Jews and perceived Jewish influence from the German economic sphere. The German government made an immediate pronouncement that “the Jews” themselves were to blame for the pogrom and imposed a punitive fine of one billion Reichsmark (some 400 million U.S. dollars at 1938 rates) on the German Jewish community. The Reich government confiscated all insurance payouts to Jews whose businesses and homes were looted or destroyed, leaving the Jewish owners personally responsible for the cost of all repairs.

In the weeks that followed, the German government promulgated dozens of laws and decrees designed to deprive Jews of their property and of their means of livelihood. Many of these laws enforced “Aryanization” policy-the transfer of Jewish-owned enterprises and property to “Aryan” ownership, usually for a fraction of their true value. Ensuing legislation barred Jews, already ineligible for employment in the public sector, from practicing most professions in the private sector, and made further strides in removing Jews from public life. German education officials expelled Jewish children still attending German schools. German Jews lost their right to hold a driver's license or own an automobile; legislation fixed restrictions on access to public transport. Jews could no longer gain admittance to “German” theaters, movie cinemas, or concert halls.

The events of Kristallnacht represented one of the most important turning points in National Socialist antisemitic policy. Historians have noted that after the pogrom, anti-Jewish policy was concentrated more and more concretely into the hands of the SS. Moreover, the passivity with which most German civilians responded to the violence signaled to the Nazi regime that the German public was prepared for more radical measures. The Nazi regime expanded and radicalized measures aimed at removing Jews entirely from German economic and social life in the forthcoming years, moving eventually towards policies of forced emigration, and finally towards the realization of a Germany “free of Jews” (judenrein) by deportation of the Jewish population “to the East.”

Thus, Kristallnacht figures as an essential turning point in Nazi Germany's persecution of Jews, which culminated in the attempt to annihilate the European Jews.

From: KRISTALLNACHT 75 YEARS ON: HOW STRONG IS ANTI-SEMITISM IN GERMANY?

By Stephen Evans, BBC News, Berlin, 8 November 2013

It's 75 years since the pogroms that became known as Kristallnacht - the night of broken glass. It was the outbreak of mass violence against Jews which was to end in their mass murder. As the anniversary is marked, how strong - or weak - is anti-Semitism in Germany today?

Ruth Recknagel remembers the feral looting. Even today, 75 years later, she recalls people swarming around the broken windows of Jewish shops in Berlin and then snatching what they could.

Ruth was born in 1930, so on 9 November 1938 she was only eight years old. She walked around the shattered glass at Potsdamer Platz with her Jewish father. What she witnessed remains imprinted on her mind.

"It was a decisive break," she says. "It was the start. From then on, everything got worse."

Series of coordinated attacks against Jews in Germany and Austria on 9-10 November 1938

At least 91 killed and 30,000 arrested; more than 1,000 synagogues burned and more than 7,000 Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged

Pretext was assassination of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath by Jewish man in Paris

Others remembered the way the pogroms unfolded into an organised orgy of violence. There was unrestrained grabbing from shops as well as attacks on schools and even hospitals. The Daily Telegraph correspondent in Berlin at the time, Michael Bruce, recounted "one of the foulest exhibitions of bestiality" he had ever witnessed when rioters broke into a hospital for sick Jewish children.

Tiny children were being chased "over the broken glass, bare-footed and wearing nothing but their nightshirts," Bruce wrote. "The nurses, doctors, and attendants were being kicked and beaten by the mob leaders, most of whom were women."

The November pogroms marked the start of the Holocaust. After it, the gloves were truly off. Jews had been persecuted from 1933 - barred from ever more jobs, routinely insulted and attacked. But Kristallnacht was the step-change in escalation. Any pretence and restraint vanished. The shattered glass of Kristallnacht led to the death camps.

And that is not forgotten in Germany today. It is taught in schools and remembered from podiums occupied by the chancellor of Germany down. But how much anti-Semitism lingers despite the knowledge of what happened?

It is a complex picture. There is, for example, a growing Jewish population in Germany. It is small at less than 1% of the total population (and much smaller than the 5% of the population with a Turkish background, for example). But it is a community which is growing rapidly, and people don't tend to migrate to a more hostile environment than the one they left.

The Israeli embassy in Berlin estimates that there are about 10,000 Israelis in Berlin alone, many of them drawn by the cultural life. The city abounds with Israeli sculptors, painters and musicians who often say they have found a home conducive to artistic creation.

There is, though, sometimes resentment from other Jews. I've been in a meeting where a visiting American-Jewish author rounded on the Israelis there who had moved to Germany to live and work. How could they look at themselves in the mirror, the angry author taunted the Israeli immigrants to Germany.

Jews in Germany often say, though, that they find much more anti-Semitism when they go abroad. One person told the BBC she had experienced far worse prejudice in Britain than she had at home in Germany - in a Cambridge college, ham was sometimes placed in her postbox.

The widely accepted research into attitudes to race across Europe was done by the University of Bielefeld. It teased out deeper attitudes by asking indirect questions about, for example, whether respondents thought Jews "have too much influence" or "try to take advantage of past persecution".

The study, published in 2011, and based on thousands of interviews done in 2008, concluded: "The significantly strongest agreement with anti-Semitic prejudices is found in Poland and Hungary. In Portugal, followed closely by Germany, anti-Semitism is significantly more prominent than in the other western European countries. In Italy and France, anti-Semitic attitudes as a whole are less widespread than the European average, while the extent of anti-Semitism is least in Great Britain and the Netherlands".

After being assaulted last year, Rabbi Daniel Alter now covers his skullcap in parts of Berlin

In all the countries studied apart from Italy, a majority answered that "Jews enrich our culture". In Germany, nearly 70% said so, about the same as in Britain.

But nearly half of German respondents said that "Jews try to take advantage of having been victims during the Nazi era". That's compared to 22% for Britain, 32% for France, 40% for Italy, 68% for Hungary and 72% for Poland.

A separate study published by the German parliament in 2012 concluded that 20% of Germans held at least "latent anti-Semitism" - some sort of quiet, unspoken antipathy towards Jews.

Rabbis often praise the German government for its outspoken condemnation of anti-Semitism. "Germany is certainly doing a lot to fight anti-Semitism," says Prof Walter Homolka, the director of Abraham Geiger College at the University of Potsdam. "Whether it is ever going to be enough, that's a big question. We can only hope to keep this figure of 20% in check."

He says the public statements and the presence of people such as Chancellor Angela Merkel at big Jewish events is important as a signal to the rest of the population. Chancellor Merkel has said that an attack on Jews is an attack on everyone.

What does seem to be clear is that anti-Semitism is rising in Germany.

"Anti-Semitism is acceptable again," says Anetta Kahane director of the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, which campaigns against racism. "It must be said clearly - those who say something anti-Semitic tacitly legitimise physical attacks on Jews."

The foundation has collated official figures which say that in 2011, there were 811 attacks on Jews. These were of various degrees of intimidation, from verbal attacks to physical assault, and included 16 violent attacks. In 2012, that rose to 865 attacks in total, with 27 of them being violent. In the first half of this year, the rise seems to have continued, with 409 attacks, 16 of them violent.

A year ago, Rabbi Daniel Alter was attacked by a group of youths of Middle Eastern appearance as he walked with his young daughter. "They made threats of violence against female members of my family, including my seven-year-old daughter who was by my side," he says.

One man confronted him very aggressively before striking him: "With his first hit he broke my cheek bone. There was another man hitting me from behind, hitting me either with his fist or something else on my head, and I fell to the floor. The next thing is I saw them running away."

It has made him change his life. Seventy-five years after Kristallnacht, he feels he can no longer wear his skullcap openly in some areas of Berlin, and covers it with a hat. And he has re-doubled his efforts to visit schools and talk to children - often alongside an Imam from a mosque.

Further Reading

Gilbert, Martin. Kristallnacht: Prelude to Destruction. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

Pehle, Walter H., editor. November 1938: From "Reichskristallnacht" To Genocide. New York: Berg, 1991.

Read, Anthony. Kristallnacht: The Nazi Night of Terror. New York: Times Books, 1989.

Schwab, Gerald. The Day the Holocaust Began: The Odyssey of Herschel Grynszpan. New York: Praeger, 1990.

KRISTALLNACHT-The Night OF Broken Glass

alfapres (15.26)

Click to return to Stories

Survivors Remember Kristallnacht:

Susan (Hilsenrath) Warsinger

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

(8.33)

The Hate Game Film 1 -- Kristallnacht

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (1.37)

Set on the streets of 'Jederstadt' ('anytown') on the morning after Kristallnacht, shows the aftermath of the pogrom against Jewish buildings, shops and people.

We see the synagogue damaged and on fire and the glass from the smashed shop windows

on the street -- it is this glass which gave Kristallnacht its name.

We see a young boy clearing the glass from outside his family's shop

when Nazi officers take away his father.

He asks their neighbour to assist him.

She chooses to not help.